There’s a big exhibition now open to the public at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario. Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Movement runs until January 16, 2022. If you’re at all interested in what Canadian artists period were producing, mainly in the between-war years, I would encourage you to see it. There’s some fine stuff on the walls, and some of it would be otherwise difficult for gallery-goers to see, either because the works are in private hands or in collections that are far from the main traffic areas of Canadian culture. I have been grappling with the very branding of the exhibition as works of the “uninvited,” in a way that I hope is not nit-picky or unsympathetic to its aims. But the grappling does help get to the nub of why this exhibition exists, and why it is worth seeing.

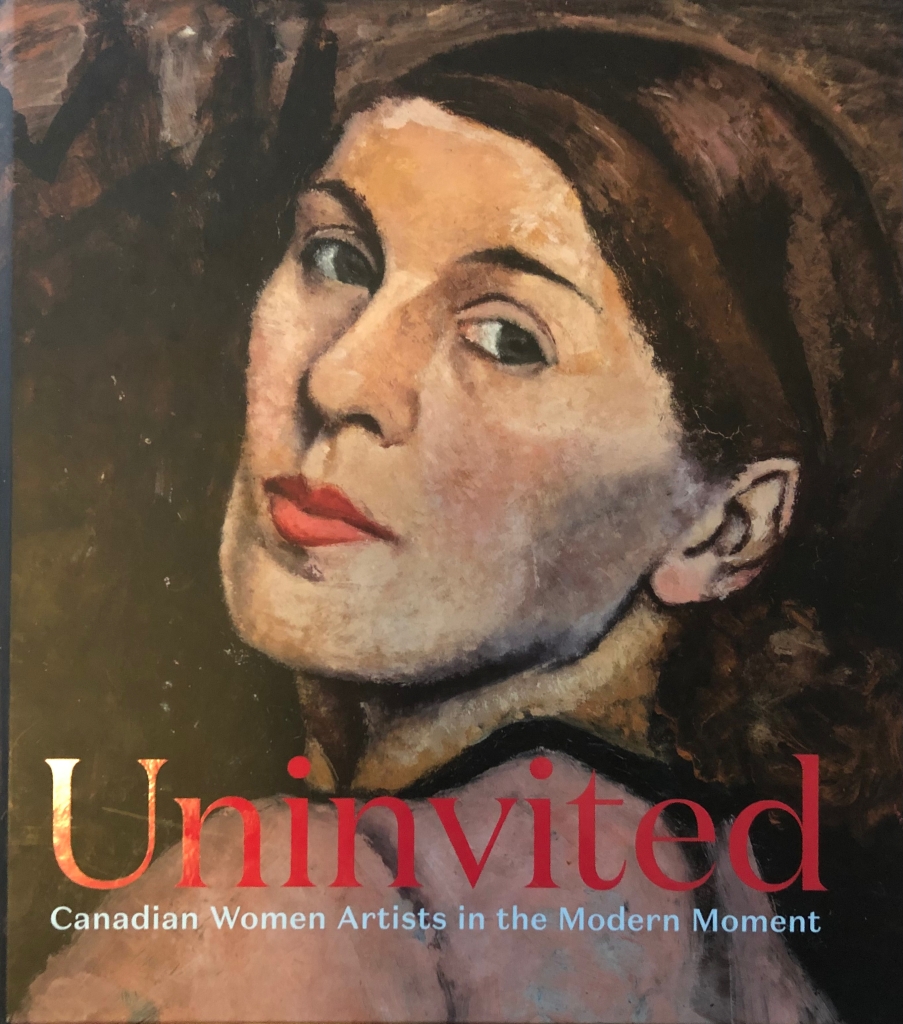

Sarah Milroy is very good, in her opening essay in the sumptuous exhibition catalogue, in the differences in experiences and opportunity between male and female artists. She also refers to artists I mention here as settler women, to distinguish them from Indigenous artists included—more on that at the end. I will leave you to peruse Milroy’s essay yourself, and instead rattle on in my own way on the exhibition’s artists.

The McMichael mounted the exhibition as a kind of counter-programming to its own (ongoing) exhibition, A Like Vision, a special installation of works from its permanent collection by members of the Group of Seven, to mark the 100th anniversary of its founding in 1920. Running at the same time is a special exhibition from the permanent collection of works by Tom Thomson, the close artistic associate of the Group’s members who most certainly would have been a member, had he not died in 1917. (A Like Vision runs until March 20, 2022, Tom Thomson until September 5, 2022.) The Group of Seven (and Thomson) were all men, and that has created a surfeit of testosterone in the public’s perception of Canadian art of the early 20th century. Certainly if the average Canadian knows anything about Canadian art, it’s what they know about the Group and Thomson.

For the McMichael, the sheer maleness of its permanent collection emerged as an issue. Robert and Signe McMichael focussed on the Group and Thomson in their collecting choices, and when they offered their gallery and its permanent collection to the government of Ontario in 1965, they owned 194 paintings that reflected this landscape world o’ guys. The collection now has more than 6,500 items, and it has been broadened to include works by First Nations and Inuit artists. But the core collection of G7-and-Thomson was deficient in its omissions, which gives rise to something of a paradox in the very title of this exhibition of Canadian women artists from the G7 period. They may not have belonged to the Group of Seven, or painted with them in various excursions, but some of the most prominent artists in this exhibition were invited to participate in Group of Seven shows as guests, and did so. The 1995 National Gallery of Canada exhibition The Group of Seven: Art for a Nation, assembled by the gallery’s curator of Canadian Art, Charles Hill, and which toured the country in 1996, included works by these guests. The support of A.Y. Jackson and other Group members for female contemporary artists is well known, and Jackson’s admiration is documented in my forthcoming book, Jackson’s Wars. The National Gallery of Canada was adding works by women who are part of this exhibition to its permanent collection, fresh from their appearance in leading society and association exhibitions.

But, to be sure, women faced limitations on their participation in professional circles, and it wasn’t just the Group of Seven that gave them a pass. Women were left out of all-male societies like the Pen and Pencil Club of Montreal and Toronto’s Arts and Letters Club (from which the Group of Seven arose), and no woman was elected to the highest rank of academician at the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts after Charlotte Schreiber in 1880, until 1933. The Group’s members emerged from male workplaces of commercial artists; as a patron, Dr. James MacCallum extended his support to members of this male professional circle. The Studio Building, built by Lawren Harris and Dr. MacCallum, rented its six studios when it opened in 1914 to men. (Marion Long did take over A.Y. Jackson’s studio after he enlisted in 1915.) Women also faced almost insurmountable hurdles in domestic expectations of the time: once married and with children to raise, a professional art career was all but over, in a way that it generally was not for male contemporaries—although Edmond Dyonnet’s protégé of promise, Henri-Zotique Fabien, was forced to abandon his painting career before the war and take a job as a draughtsman with the Department of Indian Affairs, after marrying and starting a family. British Columbia’s Sophia Pemberton (whose career predates this exhibition), was one of Canada’s great Impressionists, but her art came to a screeching halt when she married a clergyman. Even women who pursued art careers faced restraints and social disapproval. As a lesbian couple, Florence Wyle and Frances Loring (both of whom are in this exhibition), Americans who moved to Toronto before the war, defied conventions of heterosexual union and had lifelong careers as two of Canada’s leading sculptors. After seeing the bronze figures they produced for the Canadian war-art program, A.Y. Jackson declared the sculptures “make me wish to knock down all the statues in Toronto and let them replace them with anything they wish.”

In researching A.Y. Jackson’s exhibitions early in his career, I was impressed by how routinely reviews extended praise to women artists, and in anything but a condescending way. The Montreal art scene, before and after the First World War, featured a number of accomplished and well-regarded women artists. When Jackson was made an associate of the RCA in November 1914, fellow Montrealers Gertrude des Clayes and Helen McNicoll received the same honour. In reviews of group exhibitions like the annual spring show of the Art Association of Montreal (AAM) and the annual RCA show of this era, women sometimes received a separate critical discussion, even though they were not segregated into their own exhibition area, but writers otherwise readily acknowledged their strengths as artists, regardless of gender. For the 1912 AAM exhibition, the Montreal Herald praised Emily Coonan for having produced “the most masterly work of the show. There is not in all Montreal a painter who can make us feel the sincerity, the conviction, the absolute religious earnestness, of his or her work as can Miss Coonan. She belongs to no school and nobody.” She won the travelling scholarship introduced by the National Gallery in 1914, which was adjudicated by the RCA. As one of eight candidates, she beat out among others Randolph Hewton, a well-regarded Montreal contemporary and friend of Jackson’s. (There are two small Coonan works in this exhibition.) Jackson and Hewton were among the male artists in Montreal who banded together in 1920 with a sterling group of young women artists, including Coonan, Lilias Torrance Newton, Henrietta Mabel May, and Anne Savage, with Prudence Heward on the engaged periphery, to create the short-lived but noteworthy Beaver Hall Group. After the Group of Seven pulled its own plug, many of these same women joined with the Group’s members in 1933 to form the Canadian Group of Painters, which was almost equally male and female in composition.

And so we’re left to puzzle over just how uninvited these artists were. There is a strong movement afoot in curatorial circles worldwide, to recover the lost reputations of women artists. This show overlaps for example with By Her Hand: Women Artists in Italy, 1500-1800, the star of which is Artemisia Gentileschi. I think there is a basic pattern in the neglect. The fact that there is art to display reminds us that the art was being produced in the first place. Art historians, collectors, and galleries themselves, bear an historic responsibility for having overlooked, trivialized, or consigned to storage the works by women that in their day enjoyed professional standing and critical respect. I would have suggested Overlooked as a title for the McMichael exhibition, as it places the onus more firmly on the post facto neglect that set in after these artists passed, rather than the reception and standing many enjoyed in their own lifetimes.

The problem is, to a fair and acknowledged degree, the problem of the McMichael’s own permanent collection. The collection may now be multiple times greater than what had been left by the McMichaels to Ontario, but it had not moved much beyond the boy’s club epitomized by Thomson and the Group of Seven. In the catalogue’s foreword, executive director Ian A.C. Dejardin recounted drawing up “a list of every women artist I could think of” from the first half of the twentieth century in Canada as he sought to update the collection’s acquisition policy. “By no means exhaustive, the list had more than thirty names. A quick database search revealed that the representation of these artists in the collection was at best disappointing and in most cases downright pitiful.” The only female artist the McLaughlins had paid much attention to acquiring was Emily Carr. Dejardin says he “dashed off a rough first proposal for an exhibition with the title Uninvited.” The title’s inspiration seems to have been Carr’s personal experience, as she was embraced as a kindred spirit of landscape painting by Lawren Harris but then was snubbed when the Group of Seven added three new members, all male. Dejardin suggests that the exhibition concept might have gone no further, were it not for the fact that a newly appointed chief curator, Sarah Milroy, was the right person to spearhead it: “There was certainly no way that I, the white, middle-aged, entitled male of feminist nightmare, would have had the gall to curate such a show myself.”

Emily Carr has a major presence in this exhibition, but her works come at the very end, and that is for the best. Although she might anchor the idea of “uninvited,” few gallery-goers need to be reminded of who Emily Carr was and what she produced. Ask anyone halfway familiar with Canadian art in the first half of the twentieth century to name someone other than a G7 member that they would call a modernist, and they’re probably going to say Emily Carr or David Milne, long before they summon the name of someone like Lilias Torrance Newton or Prudence Heward, two Montrealers who to my eye are star attractions of Uninvited. Despite their relative standing, Torrance Newton and Heward are probably going to be fresh discoveries for a lot of exhibition-goers. It was only about 2015 that the National Gallery of Canada made a significant change to its 20th-century Canadian galleries, dispatching to storage the decorative panels that future G7 members (and Thomson) created for Dr. James MacCallum’s Georgian Bay cottage and in their stead filling the side gallery with a marvellous assortment of works by Torrance Newton, Heward, and other women who were producing outstanding portraiture after the First World War.

The distinction between landscape and portraiture is not lost on the contributors to the exhibition catalogue. Many of the artists included excelled or specialized in portraiture, especially of women. On the one hand, the specialization recalls the mastery of Impressionists Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot in depicting mothers and children. On the other hand, Torrance Newton and Heward’s portraiture is intensely psychological, to the point of severity. Women artists did venture out of doors, as works by Anne Savage, Marion Long, Regina Seiden Goldberg, Laura Muntz, and others show. But in the early twentieth century, as a renewed call arose from within Toronto’s all-male Arts and Letters Club for a distinctive Canadian art anchored in the landscape, the exercise was routinely cast as something explicitly male in energy and temperament. American landscape art at the time had a similar obsession with ideas of male virility and engagement with the terrain. The very model of a Canadian landscape artist, after the Group of Seven arose, was the painter-as-bushman, for which the late Tom Thomson proved iconic. Journalist Fred Housser would insist in his 1926 book on the Group of Seven, A Canadian Art Movement, “The task demands a new type of artist; one who divests himself of the velvet coat and flowing tie of his caste, puts on the outfit of the bushwhacker and prospector; closes with his environment; paddles, portages and makes camp; sleeps in the out-of-doors under the stars; climbs mountains with his sketch box on his back.” How delicious, then, to see in this exhibition works by Housser’s own wife, Yvonne McKeague Housser, as an emphatic counterpoint to the championing of the virile male gaze. She may not have bushwhacked like Thomson, but her marvellous, luminous depictions of the mining town of Cobalt, Ontario are as good as anything that Group members themselves managed in the way of depicting the peculiar industrial/residential rusticity of northern factory towns. Little wonder, as Sara Angel’s essay notes, that she was asked to join the Group as a guest for three exhibits.

That obsession with an exclusively male gaze was exacerbated by war-art commissions. Only men, in the British and Canadian war-art programs (including two future members of the Group of Seven, A.Y. Jackson and Frederick Varley), got the plum assignments right up at the Western Front, which came with honorary officers’ commissions. Women did secure assignments on the home front, but when Canada emerged from the war, it was the all-male circle of the Toronto Arts and Letters Club and the tenants of the Studio Building funded by Lawren Harris and Dr. James MacCallum that picked up where the landscape movement’s momentum had been blunted by the declaration of war, and created the Group of Seven. G7 members like Jackson and Arthur Lismer may have been great supporters of female colleagues, but middle-brow Canadian tastes, especially since the 1970s, were destined to almost fetishize the Group’s output, at the expense of the longterm reputations of those colleagues. Gallery shops in Canada abound with knick-knacks featuring G7 paintings, good, bad, and indifferent, from placemats to coffee mugs, while outstanding works by their female colleagues have in some cases been difficult to even find on the walls of galleries that owned examples.

Galleries are getting better at exhibiting these artists, who have also benefited from fresh evaluations like Concordia University’s Canadian Women’s Art History Initiative, a terrific online resource. The value of this exhibition is seeing artists and works otherwise unknown to or under-appreciated by most gallery-goers, myself included. I was mainly interested in seeing the works by Torrance Newton and Heward, whose canvases were already somewhat known to me (and both women figure in the narrative of Jackson’s Wars.) I would have hoped to see more than the two smallish works by Emily Coonan, but there were compensations elsewhere. Yvonne McKeague Housser, I have already mentioned. As someone who works in black and white myself, I was impressed by the Georgian Bay drawings of sculptor Elizabeth Wyn Wood. Winnifred Petchey Marsh’s watercolours of Inuit camps in the 1930s were entirely new to me, and far exceeded whatever expectations one might have for the output of an Anglican missionary’s wife, but she was a trained artist, and these works, in the collection of the Northern Heritage Centre, are wonderfully fresh.

In closing, I will return to the differentiation by Sarah Milroy between settler women artists and Indigenous artists. The show is mostly about those settler women—mainly from middle to upper-class backgrounds, trained at art schools in Europe or in schools with European traditions, active in the same society exhibitions as settler men, and with clients within that milieu of class and society. In stark contrast are the works of Indigenous women, including the extraordinary beadwork of Attatsiaq and Elizabeth Katt Petrant, and a host of baskets, moccasins, and other historic pieces by unknown creators. To say that there is a gulf of experience and standing between these artists and the settler women is an understatement. Gender has brought them together in one exhibition, but they are otherwise worlds apart. Perhaps the Indigenous women have been the truly uninvited, where the world of galleries, art societies and groups, and clientele are concerned. Including their works, however anonymous many pieces are, elevates their creations from mere “craft” or the ethnographic concerns of anthropology collections.

We could spend days mulling over the differences between creative acts meant to be worn and otherwise utilized, by family and community, and art in the western sense that has been created purely for display, and whether by placing works of other cultural processes purely on display, we can appreciate them without losing sight of, or respect for, what they are and what they would have meant to their creators and wearers or users. It has been argued that modernity in art began when works became objects unto themselves, creative acts that were no longer valued or judged purely on the basis of how faithfully they depicted some subject. Somewhere in this tangle of utility/creativity are lessons about how we bring together objects from disparate cultures, processes, and intentions, but for now, it is pleasure enough to find them in the same room.

Leave a comment